1772-1821

Spanish CaliforniaThe Spanish Imprint 1769-1821

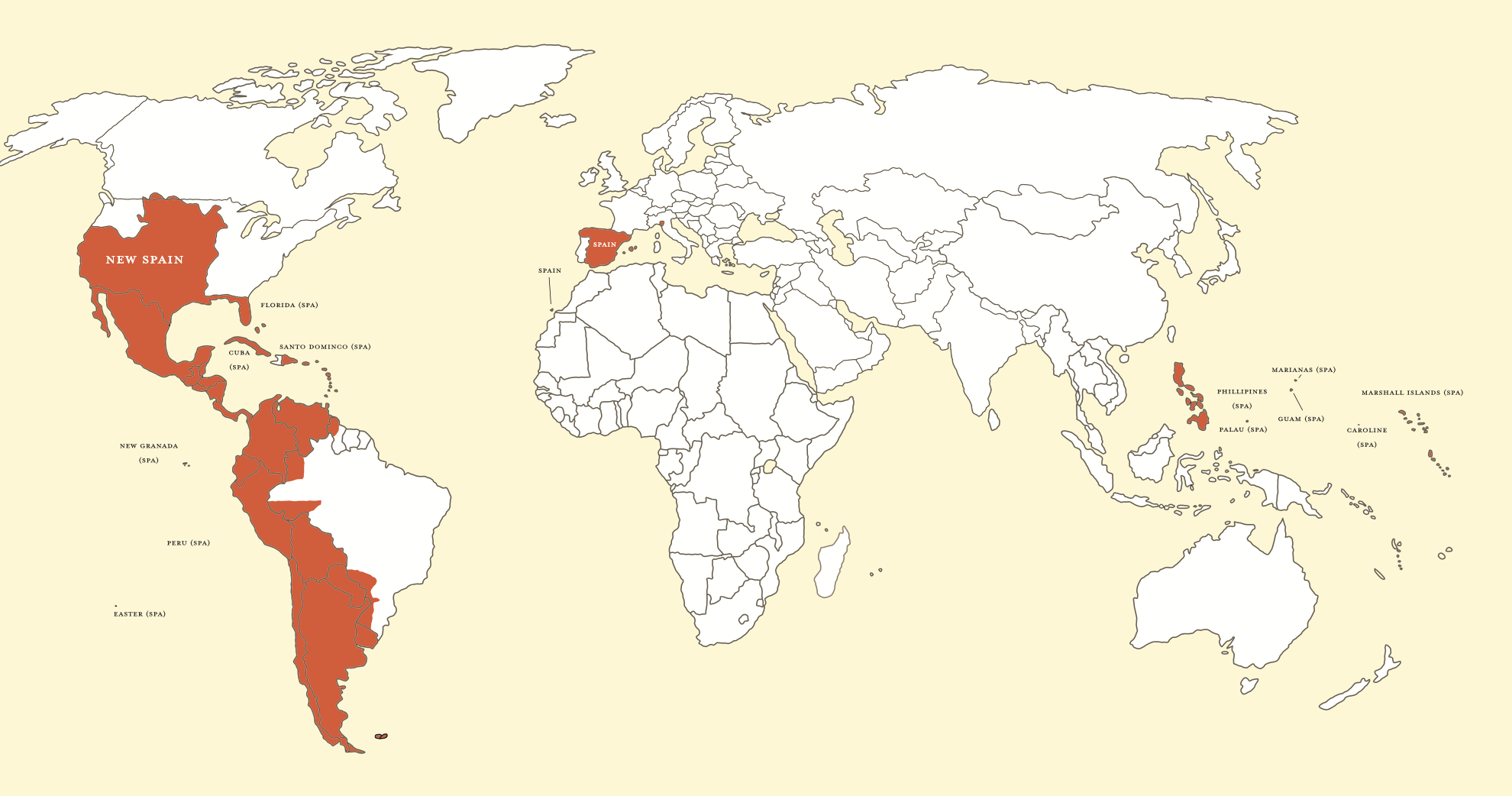

At one time, the Spanish empire stretched from the Philippines to various parts of western Europe; in addition, Spain’s monarchs claimed the islands of the Caribbean, Florida, and the arc of territory that extended from present-day Texas to Oregon, as well as the lands from the straits of Magellan to San Francisco Bay. At the northern edge of this vast empire, in what Spaniards called Alta California, lay the central valley.

Soon after 1492, a Spanish expedition led by Hernan Cortes entered Mexico in 1519 and encountered the dominant native power, the Mexica (Aztecs). In 1521, a coalition of the Mexica’s indigenous enemies, along with Cortes’ soldiers and Spanish reinforcements, vanquished the Aztecs.

The gradual penetration of Spanish influence and the Catholic religion ensued, though in a highly uneven process. The spread of European-borne diseases (such as measles and smallpox) and the harsh use of natives as forced labor devastated indigenous populations, especially those close to mining operations and/or rich agricultural lands. In remote areas, the Spanish intrusion took much longer to take hold.

The size of the empire came at a huge cost, and more so once large silver deposits were discovered in north central Mexico by 1550. The Spanish crown spent enormous sums in defense of its trade routes and in guarding royal interests, including strict rules over the approval of expeditions, land grants, and immigration from Spain. Thus, the Spanish monarchy concentrated its resources on protecting its most valuable colonial commerce, but conflicts with European rivals drained much of the crown’s wealth over time; by the middle of 18th century, the once mighty Spanish empire had become a shell of its former power.

Early on, Spanish explorers failed to find silver, gold or other valuable resources in the northern rim of Spain’s American empire—what became Texas, Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada and California. As a result, the Spanish crown basically neglected Alta California for nearly 250 years; it was not until 1769 that Spanish authorities approved the settlement of the region leading to the founding of the first mission in San Diego. Spain’s inability to provide attractive incentives to settlers, however, meant a string of missions, a few small coastal towns and far-flung ranchos with scarce markets to fuel local economies. The missionary effort produced paltry results: rather than staying in the missions or in adjacent lands, many indigenous peoples fled to the interior, often taking with them European-borne diseases. Meanwhile, invasive plants, introduced by feral livestock, negatively altered the environment and consequently undermined the livelihoods of the valley’s native groups. As a consequence of the Spanish presence, the human and physical ecology of the central valley deteriorated.

With the upheaval generated by the French revolution 1789 and its repercussions, Spain lost nearly all of its colonies in the Americas, including what became Mexico in 1821.

By Dr. Alex Saragoza

Native Valley

There are places in the Northern San Joaquin Valley of Central California where the curious can still get a feeling for what this vast fertile plain was like before the Spanish arrived to explore it, the trappers to exploit it, the Mexicans to settle it and the new Americans to cultivate and mine it for its wealth.

Near Gustine in Merced County, when the winter has been wet enough, a canoe trip through the undeveloped Grasslands State Park reveals wildflower panoramas, flocking and nesting birds, swamps, sloughs and starling views of the snow-covered Sierra in the distance. In the winding California Delta waterways, where the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers entwine as they braid their way toward San Francisco Bay and the Pacific Ocean, a sense of the tule marches can still be found. And along the lower Stanislaus River, between San Joaquin and Stanislaus counties, a narrow ribbon of protected vegetation reflects the once-teeming riparian jungle of oak, sycamore, cottonwood, ash and alder, all canopied with wild grapevines and burning with an understory of willows, berries and brambles.

Before railroads and roads, canals and dams, power lines and telephone lines, before land leveling and drainage, before plows, pumps and agriculture—the flood-watered landscape of sloughs and swamps swarmed with wildlife.

There were hawks, egrets, eagles, herons, cranes, vultures and condors. There were herds of tule elk, pronghorn antelope and deer. The rivers were literally “crowded with salmon.” Grizzly bears were common, as were minks, weasels, otters, racoons, fox and beaver, badgers, skunks, coyotes, rabbits, mountain lions and bobcats. Ducks, geese and swans considered the valley their winter home–they were the international migrants. Tiny songbirds migrated, too. They clung to the stream sides as they followed the seasons up and down the Sierra slopes.

Amid this abundance, Indians wore their trails and made their homes. The valley was a crossroads for aboriginal trade and the center of Indian communities that measured their lineage from the mists of antiquity.

From The Stanislaus Indian Wars, Thorne B. Gray

Photograph Grasslands State Park

Valle de los Tulares

When the Spaniards entered the central valley of the Yokuts and Miwoks over 250 years ago, they found a much different landscape than the one today. Areas to the north were characterized by vast riparian forests and large marshes, fed by seasonal surges from its mountain snowmelt to its streams and tributaries. In the central area, the San Joaquin River wound along the once-barren western side and parched prairie where they first would drain natives for the coastal missions.

In the southern region mountain rivers drained into a basin, forming what was said to be the largest lake west of the Mississippi. In wet years Tulare Lake resembled a sea covering large sections of the south valley, expanding and contracting during seasons, and sometimes no more than six feet deep. Huge tule-filled swamps around the lake gave the valley its Spanish name Los Tulares and frustrated the Spanish explorers with large mosquito infestations, breding malaria.

Large parts of the valley were often underwater, particularly during the rainy season and after the melting of the Sierras snow which drained into rivers, marshes, swamps, lakes, and ponds. Teeming with fish and wildlife, it was a great expanse of prairie grasslands and tule grass marshes, with lakes hundreds of square miles in size strung out along the valley axis. wetlands bordered by arid to semi-arid areas, even alkali desert in places. The abundant game beckoned trappers and mountain men, but first the Spanish soldiers and missionaries hunting deserters and native souls.

The first Spaniards to view the Valley in 1772 entered from the southern pass at Tejon, climbed to Mount Diablo and saw “the land opened into a great plain as level as the palm of the hand…as far as the eye could see,” (Father Juan Crespi.) Commander Pedro Fages called it Buena Vista in his diary, “with numerous reed patches and ponds and an abundance of fish, birds, and wildlife and various species of edible plants.” Their descriptions encouraged further explorations.

Camino Viejo a Los Angeles

Although much of California’s history in this period is along the missions, El Camino Real, our valley story follows El Camino Viejo. This road, following old native and older antelope trails, skirted the eastern slope of the coast range foothills, leading from one water hole to another. To the early Spanish explorers and settlers this road was known as El Camino Viejo a Los Angeles.

The road served also as a refuge trail, enabling Spanish fugitives unobserved by the coast settlers to pass from El Pueblo de Los Angeles to the San Francisco Bay region. The route and watering stations, known for their Spanish names aguaje (watering place) and arroyo (creek), traveled through tule swamps and alkali plains and took about 60 days at the rate of one mile an hour.

The trail worn by animals, inhabitants, then horses and cattle and Spanish carretas, carved a path through the center of California and developed villages, pueblos, towns and places known for their defining characteristics and history.

Key Stops El Camino Viejo, South to North

Begins San Pedro Harbor, passes by El Pueblo de los Angeles, Rancho Los Feliz, San Fernando Rey de España, Cahuenga Pass, San Francisquito Cañyon, La Laguna de Chico López, Portezuela de Cortés, Cañada de las Uvas, Rancho de San Emigdio.

Skirts the western shore of Tule Lake, Laguna de Tache, largest fresh water lake west of Mississippi River and home of Tache Yokuts, on for 250 miles along the Mt. Diablo mountain range, following the foothill route. During winters of sufficient rainfall, one of the most beautiful regions of Alta California, but during summer and springs of the años secos, a dreaded ordeal.

Follows Buena Vista Lake and hills, Arroyo de Amagosa, La Brea village called Asphalto (later prehistoric digs), Aguaje de Santa María, Rancho Temblores, Arroyo de Chico Martínez, Aguaje Lodoso, Aguaje Mesteño, Aguaje de los Encinos.

Arroyo de los Carneros, rocks 600 feet above the valley, a guide for travelers and caves for natives, passes Agua de en Media, Agua del Diablo, Arroyo de Matarano, crosses the old trail from Paso Robles to Tulare Lake, Corral de Matarano, Las Tinajas de los Indios.

Aguaje La Brea, a few feet off the road from Paso Robles to Hanford and site of one of first producing wells in the San Joaquin Valley, passes Alamo Solo, site of a native village, Immigrant Peak, where there’s a discovery of prehistoric oyster shells, then Aguaje de Caballo Blanco, crosses trail to Tulare Lake, ending in present day Coalinga.

Vaca Adobe, Indian village and in 1863 a camp established by sheepherders from New Mexico, in the late 1890s a steamboat landing on Tulare Lake and an Old Gilroy-Fort Tejon stage road.

Las Juntas (the junction), on San Joaquin River near Mendota and later known as Fresno or Fish Slough, passed Arroyo de Panoche Grande and connected with the western branch of El Camino Real, passing Arroyo de las Garzas (Kettleman), Las Canoas, Las Polvaderas.

Poso de Chine, site of an Indian village, the only Spanish settlement in Fresno County with twelve Spanish and Mexican families, near Coalinga, but obliterated by flood in 1862.

Arroyo de Cantua, where later Joaquin Murrieta and his followers built an adobe, passes Arroyo Hondo, Arroyo de Panoche Grande, Arroyo de Panochito, Arroyo de las Ortigalitas.

Arroyo de los Baños del Padre Arroyo de la Cuesta, a bathing and resting place on trips from San Juan Bautista mission to the San Joaquin Valley, about 7 miles south of the current Los Baños, also known as a large Indian encampment.

Arroyo de San Luis Gonzaga, Pacheco Pass, Centinella, outposts for Spanish stockmen who lived at Monterrey and San Juan. An adobe building at Centinela from 1810 until 1900 a vaquero camp, Agua de los Mesteños, Las Garzas west of Gustine, an old adobe occupied as late as 1850 by a mestizo deserter from the Spanish cavalry and later known as Newman Sheep Camp.

Arroyo de Orestimba (place of rendezvous), where Spanish padres collected the first Yokuts to take to San Juan Bautista and made plans to meet the natives there again the following year.

Passed Arroyo de Salada Grande, Arroyo de la Puerta, Arroyo de Hospital, Buenos Aires, then left the San Joaquin Valley for Altamont between Tracy and Oakland, Arroyo Seco, Las Positas,

San Lorenzo, ended in east Oakland.

__________________________

Source: El Camino Viejo a Los Angeles, Frank F. Latta, Bear State Books

Latta became an early valley historian through interviews he conducted in the 1930s with rarely settlers.

The Spanish soldiers and friars were the first Europeans to enter our valley. They brought with them the language, religion, armament, institutions, livestock, and plants from the Spanish empire. They also brought their own seed, sown through century of conquests in Mexico, and diseases for which the native population had no immunity. One indelible imprint was the naming of our rivers, valleys and regions. Cattle and mustang horses proliferated in the valley.

Spain would not allow free movement in the colonies. All expeditions needed the King’s approval. The population of Spaniards was pitifully small and, had it not been for native guides, the explorations and settlements would not have been possible.

For the Yokut and Miwok natives of the Central Valley, the encounter with Spanish soldiers had arrived, as the continent had faced for almost 300 years. The native peoples would be ravaged by the diseases and the changes to the land, plants and animals as a result of the clash. Their fate haunts the diaries of the soldiers and missionaries. There were an estimated 70,000 to 100,000 native peoples throughout the greater valley area, unknown territory on Spanish maps, Tierra Incógnita. It was an exploration and an invasion.

Expeditions came into the valley mostly through the south at Tejon Pass and skirted the west side of the valley. Another trail emerged from Mission San Juan Bautista to Los Baños used mainly for capturing deserters, runaway mission natives, and forcibly taking natives to the coastal missions. Explorations of the valley recorded in diaries, reports, and church records give us a Spanish version of the encuentro, but read between the lines. Native tales and statistics tell other stories.

At the time of the American Revolution on the East Coast

1772

Spanish explorer Pedro Fages entered the valley in search of deserting Spanish soldiers. He described the abundance of fish, birds, and wildlife and various species of edible plants. Without the means of controlling waterways, large parts of the valley were often underwater, particularly during the rainy season and after the melting of the Sierras snow. Huge tule-filled swamps covered sections of the Valley, giving it the name of Los Tulares.

1776

Father Francisco Garces explored the southern area of present- day Kern County to Woodlake and Visalia and then returned to Sonora Mexico. He recorded observations and information on native peoples, but most of his journals recounted conversions.

José Joaquín Moraga and others crossed from Monterrey to explore the northern areas three times in the year, finally venturing into the Fresno region up to the Stockton area. He named the Rio de Pescadero, the Río San Francisco Javier, the Río San Miguel, and the Rio de la Pasión.

Optimistic Reports from the Valley were Eclipsed by Efforts to Establish the Coastal Missions and Pueblos

1800-1814

During the administration of Governor José Joaquín de Arillaga excursions into the valley accelerated. There was renewed interest because the mission system was already well established by 1800 and Russians had erected a settlement in northern California, representing a danger to Spanish claims. Many native peoples found life at the missions intolerable and left for the interior.

At times they attacked settlements, stole horses and firearms, and posed an undesirable example to others who were yet to be taken to the missions.

1804

Father Juan Martín ventured into the Tulare area to seek a mission site, but he found it would be hard to hold. Conquest to the Franciscans meant spiritual conversion. They referred to native peoples as “heathens” if not baptized and “neophytes” if baptized in the missions. At first, some natives came willingly, but the slightest discipline was irksome.

“As soon as I arrived they presented me with their little sons so that I might carry them away to be baptized…Seeing such a harvest, your reverence may well imagine how happy I was at the prospect of gaining so many infant souls for paradise.” But alarmed at the number of Indians sick or dying, he reported “If a mission is not placed among them soon, when one is established there will remain no one to convert.” Fr. Juan Martín

The Idea of an Inland Mission Gained Favor and Support

1805-1810

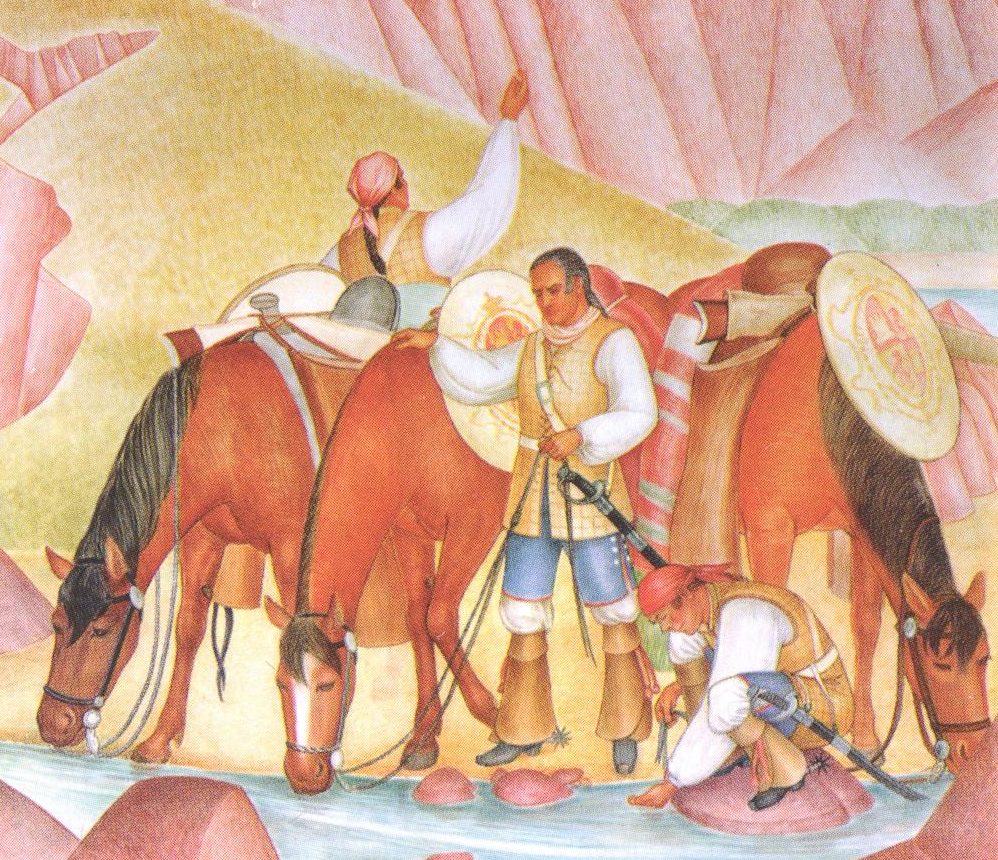

Gabriel Moraga, the valley’s most significant Spanish explorer, made several major trips into the valley to seek fugitives, record features of the land, and seek a possible site for a mission.

He named the Río de San Joaquín and Río de Los Santos Reyes (Kings) rivers and eventually the valley itself for his father and earlier explorer, José Joaquín Moraga.

He led expeditions with Fr. Pedro Muñoz and 20 soldiers to the present Firebaugh, Dos Palos and Chowchilla areas, a land of overflow and butterflies–Mariposa. He turned north and named the Río de la Merced (Merced River). Others in his party reached the present-day areas of Millerton, Laton and Reedley, then reunited with the other party in Visalia. They explored the Kaweah River, the Kern River and the Porterville area, then left for the south, recording they found 24 villages and over 5,000 native peoples.

1806

Francisco Ruiz and Father José Maria de Zalvidea entered the southern valley Kingsburg area and camped in an oak forest near Visalia, maybe the present Mooney Grove.

1810

Moraga had recommended a site a site for a mission on the Merced River in an earlier expedition, but by his later journey decided better a site in the Visalia area.

Mexico Declared Independence from Spain in 1810— and didn’t win it until 1821

1811

Jose Antonio Sanchez and Padre Abella went by boat up the San Joaquin River and back. Two years later Francisco Soto explored for a mission site with 100 mission natives and ten soldiers, ending in a bloody battle with 800 natives. Then José Arguello led an expedition of punishment reporting that a thousand hostiles were concentrated on an island protected by dense thickets. The party forced the natives to flee with heavy casualties, while they suffered the loss of only one native ally. Soldiers had the advantage because of their thick jackets of layers of cowhide, which arrows could seldom penetrate.

1814

Father Juan Cabot visited Rancheria de Tache, native village along the Kings River, to recover neophytes and look for a mission site. The next year José Dolores Pico, Sergeant Ortega, and Father Cabot, commanded a party into the valley through Mendota to the Kings River in the Tulare region, also looking for a mission site and fugitive natives. When they found a village, the natives had killed over 200 horses for the meat. They left with 65 captives, mostly women, but the native guides helped some of the captives escape on the way back.

1815-1822

Father Mariano Payeras became president of the Franciscan missions from 1815-1822 and urged Spain to approve a valley mission and presidio. Fr. Luis Antonio Martinez was sent to Los Tulares, recommending a site in the northern Kern area, but was rejected and only able to obtain one boy “in exchange for beads, blankets and meat.” He returned discouraged.

1817

Fray Felipe Arroyo de la Cuesta of the San Juan Bautista (known for bathing in Los Baños on his trips, noted that the natives were escaping into the valley and joining others to come back and raid the missions for livestock and horses and liberating other mission natives. The Spanish raiders were now being raided.

1818-1820

Governor Sola sent three expeditions in this time, with money and arms to the missions and troops to the presidios. The last official expeditions of José Antonio Sanchez in the northern area and José Dolores Pico with José María Estudillo from the south was to subdue hostile natives.

Spain’s Hold Deteriorated and the Native Resistance Worsened

Thirty years after Moraga’s expedition into the valley, Spain’s empire in the Americas finally disintegrated with the impact of the French Revolution of 1789 and the invasion of Napoleon into Spain. Although they saw themselves as bringing God, Glory and Civilization to California, they began the destruction of a civilization already here through diseases, war and cultural trauma. They gave Spanish names to many places. They introduced cattle and horses, language, and laws—and destroyed much of the environment through devastation to native plants and animals. Although they had come to the Americas to seek gold, they left just 27 years before the great discovery here.

In all, the Hispanic peoples in the valley in this period numbered no more than about 250 soldiers and missionaries named in the expeditions here, plus an unknowable number of mestizos they left during their 49 years stay.

Natives, on the other hand, were reduced by two thirds their former size.

GABRIEL MORAGA, VALLEY’S MOST NOTABLE EXPLORER

Of the relatively few Spanish soldiers assigned to explore the interior, Gabriel Moraga is significant to the valley for his discoveries and the names he gave them, most of all for CAMINOS, the San Joaquin Valley itself.

The Spanish Imprint on the Valley

Spain’s rival colonial empires England and France also made claims in the new lands, but the Spanish excelled with fierce passion and religious ferocity. While many other European nations were still fighting over eastern trade, the Spanish American colonies helped make Spain one of the richest and most powerful nations for over 250 years and five generations.

What took Spain so long to get to Alta California?

Despite Cabrillos’ exploration and claim of the California coast for Spain in the exploratory voyage of 1542, Spain’s presence in the northern frontier of its empire in the Americas was weak, After the Spanish settlement of Santa Fe in 1598, it was another 171 years before the founding of the first mission in San Diego in 1769. Resources were stretched.

Throughout the 16th century, Spain increased its military might, but not without conflicts and crisis in defending their imperial interests. During first Hapsburg Dynasty from 1516-1700 and later the Bourbon Dynasty from 1700-1830, Spain spent much of its wealth in the effort to first suppress the Protestant Revolution and then the Islamic Ottoman Empire’s challenges. There were European rivals on land and sea into the early 1800s—the Dutch, English, French and Portuguese. And then there was the periodic ineffectual monarch on the Spanish throne and or inept financial management which added to the challenges the empire faced those centuries.

After 300 years in the Americas and toward the end of their colonization of Nueva España, Spain finally authorized exploration into Alta California with soldiers and missionaries to counter encroachments along the northern part by British and Russian traders. The difficulties of developing settlements were many, the approach used to create missions, presidios and pueblos along the coastline. Even maintaining a supply chain was made difficult in sailing north against currents. Added to all these obstacles, the Sonora-California trail was dangerous as an overland route due to the power of the Comanche.

1769-1770 Portola´s "Sacred Expedition"

While the American Revolution was fomenting on the east coast, Gaspar de Portola set out with Father Junipero Serra by land to Alta California to establish the foothold, beginning with a site for a mission in San Diego. Portola, along with Sergeant Ortega, scouted north as far as San Francisco Bay and turned back to establish the capital in Monterey. Portola, already governor of the lower Baja California, became the first governor of Alta California. Others in the expedition would also be part of the later exploration of the central valley—Capitan Pedro Fages and Fr. Crespi. Serra’s founding of the mission in San Diego would be the first that by 1823 had established 21 along the coast.

1769-1770 The Anza Expedition

On the eve of the American Revolution, Spanish Lt Coronel Juan Bautista de Anza led more than 250 men, women, and children 18,000 miles overland across the frontier of New Spain to establish a settlement in the San Francisco Bay. Joaquín Moraga and his family were in that expedition, a soldier whose name would ultimately be given to the Valley by his son and explorer Gabriel Moraga.

1772-1819 Exploration of the Valley

While most attention and resources were concentrated on the coast, the interior valley was Tierra Incognito on the maps, unknown territory to be explored. The first expeditions into the valley were to capture natives for the missions and to chase runaway natives and soldiers. Key explorers during this first period were Pedro Fages’s and Joaquín Moraga, with the priests and diarists accompanying them.

When Spain later approved expeditions to explore interior, the most notable were led by Gabriel Moraga’s from 1806-1810. During the same time, the American states were exploring their acquisition of the Louisiana Purchase from the French in 1803 with the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1808.

Spain’s hold was at its weakest, Mexican ideas of independence were fomenting, and the United States already had its eyes on Western expansion.

Meanwhile Spain’s American colonies were drifting away, giving rise to a tide of New World revolutions that swept away nearly all its American colonies. After several decades of Spain’s decline, precipitating the break in 1808 was Napoleon’s occupation of Spain, forcing Carlos IV and his son Fernando VII to renounce their rights to the crown and leaving Spain without a clearly legitimate ruler. The French occupation and an English blockade that cut off trade between Spain and its colonies caused a collapse of colonial trade and revenue that, together with the expenses of war, ruined the Spanish economy.

In Alta California, Spain’s crisis in Spain and the violent rebellion in 1810 in New Spain (Mexico) had disrupted commerce, shut off supplies for soldiers and missionaries, diminished the flow of goods for trade with natives, left unpaid salaries of government officials and made smuggling a necessity. After the American Revolution of 1776, Spanish colonies in the Americas erupted against Spain’s colonial grasp, too weak to hold the empire and left in 1821.

The Spanish Side of the Story

The Spanish did not come to wage war and eliminate the native population, although their intentions went terribly wrong, and they ended up doing much of that. They saw themselves as bringing God and glory and civilization to their colonies in the Americas (while mining it for the riches.) They established missions and attempted to convert natives to Spanish subjects (and workers). They relied on incentives, food and beads and a policy that intended to give back the lands to hispanized native peoples after they were developed by Spanish-speaking settlers.

They brought the Spanish language and Catholic religion, their institutions and law. They gave names to rivers and places and introduced horses and cattle and horsemanship itself. They introduced plants from Spain, olives, oranges, and fruits. This was their imprint, along with their DNA left in succeeding generations. Their legacy was complicated by diseases they also brought and the ultimate destruction of native plants and animals–and natives themselves.

Encuentro: The Native Side of the Story

To the native populations, the Spanish proved to be an invasive species, along with their animals and plants. They spread diseases for which natives had no immunity—smallpox, diphtheria, influenza and syphilis— and contributed to the initial decimation of the native population through diseases, abuse, warfare, and colonial subjugation. Native peoples progressed from wonderment or terror at these “whitefaces riding on big dogs” and wielding weapons that could overpower them to increased resistance and adaptation to horse culture and weaponry.

Archeological records indicate there were native populations in the valley 10,000 years ago. In the total length of the central valley there were over 50 triblets, most Yokut and Momo in our focus. Gabriel Moraga estimated around 280 average persons per village. Scholars estimates up to 300,000 in all California. Most natives in the northwest side of the Valley were removed in the first years to supply the missions. Some, located south of the San Joaquin River, melted away into territory inaccessible to white men. Near the shores of Lake Tulare and into Kings county Yokut tribes traded and joined in hunts, Monos kept mostly to the eastern Sierra. We refer to them in this history as native populations, they weren’t then neither American nor Indian. In the Spanish period they were “neophytes” if baptized and “heathen” if not.

It is irony that the Spanish never found the gold that would be discovered in the valley 27 years after they left. Today the names of some tribes survive in Casinos—Mono, Chuchanski, Tachi, and in the names like Kawia. For the most part they were Yokuts, “the people.” In the Tulare and Kings counties area they were lake peoples, Chu-nut, Wowol, Tachi. Some of what we know of them is from the interviews with later generations by Frank Latta in the 1930s. Bob Bautista was the last Tachi medicine man and the last surviving member of the Wowlumne Yokuts. He died in 1923. His grandfather swam the Kern River with Padre Garces in 1776.

Mestizo

The population of Alta California became increasingly mestizo (mixed), the combination of natives and Spaniards, already mestizo themselves. Spaniards brought very few women to the Americas and were partially successful in colonizing the lands they occupied by taking native women as wives or mates, with some encouragement from the Spanish crown, as long as they were Christianized or from a noble native tribe. Those who maintained Spanish ancestry, so very few after 200 years of mestizaje in Mexico, were referred to as criollos in the Spanish casta system. Contrast this with the English pilgrims who mostly avoided intermixing, although some of the success of the later European trappers was through taking native wives, thus entering tribal families. Native and mestiza women were essential to colonization virtually all settlers and soldiers from the Spanish period were not, in fact, born in Spain. They were overwhelmingly mestizo, criollos, second or third generations removed from their Spanish forefathers.

Bookmarks

The Spanish Frontier in North America, David J Weber, Yale University Press, 2009

Foreigners in their Own Land, David Weber

El Camino Viejo a Los Angeles, Frank Latta 1932 interviews

The Great Central Valley, Gerald Haslam, et al.

The Comanche Empire, Pekka Hamalainen, Yale University Press, 2008

The Land Between Rivers, documentary on Fresno County

For documentation of the Portola and Anza expeditions, documentsmilitarymuseum.org/Portola Expedition by the California Historical Society, and webdeanza.org