1822-1848

Mexican CaliforniaLOS CALIFORNIOS

The Mexican Period 1822-1848

After a highly destructive struggle for independence, the new nation of Mexico faced enormous challenges: most mines were inoperable; much agricultural production in ruins; livestock herds decimated; bridges and roads in disrepair; commerce in disarray. A nearly bankrupt treasury forced the fledgling government to borrow heavily for foreign sources. Political differences made governance difficult and unstable. Between 1822 and 1846 there would be more than forty changes of presidential administrations. The successful revolt in 1836 by settlers in Texas (most of them from the U.S.) reflected Mexico’s weaknesses.

As a result, Alta California remained essentially isolated from the country due to the arduous, distant lines of communication, the lack of commercial shipping, and the presence of hostile natives, especially the Comanche and Apache, along the land route to Mexico.

Still, the Mexican government attempted to attract settlers to Alta California through land grants, most of which were allocated near the coast, but very few were made in the central valley. The sparse Spanish-speaking population stunted the economic promise of the area. Livestock, mainly cattle, roamed the lush, fenceless meadows, joined by feral horses that had escaped from coastal settlements and ranchos. In a sense, the central valley functioned as a huge corral. Mexican cowboys (vaqueros) periodically conducted round-ups (rodeos), mainly for the hides of the cattle (to make leather) and for the capture of mustangs—leaving a vocabulary and heritage of horsemanship still evident today.

The environmental effects of this “corral,” however, held detrimental effects for the indigenous peoples of the valley. Streams were despoiled by feral livestock, native grasses succumbed to invasive plants, and topsoil washed away from overgrazing and the furrowing of hillsides by hoofed animals.

The Mexican era of Alta California ended within a brief twenty-six years. The architectural remnants of the Spanish and Mexican presence along coastal California stand as stark reminders that no such patrimony exists in the central valley. The restored missions and historic adobes along California’s “camino real” represent unintentional monuments to Mexico’s travails by 1845: without sufficient treasury to equip an adequate army or naval force, the young nation found it impossible to protect effectively its extensive geographic expanse. The country proved vulnerable to an assault on its territory—the neighbor to the north soon seized the opportunity to acquire what it had coveted for decades. The war between the two unequal nations—the population of Mexico was about seven million at the time, that of the U.S. was about twenty million–lasted two years, ending with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848. As a result, Mexico ceded its northern territory, about half of the country, including Alta California, to the United States.

By Dr. Alex Saragoza

This period writ large begins and ends with war–war against colonial Spain, the natives of La Frontera, for its territory of Texas, and then the advancing Americanos.

Mexico threw off the yoke of Spain in 1821, but the new nation only held Alta California for 27 years.

As early as 1808, Spain’s American colonies began to fight for their independence in the midst of the upheaval in Europe as a result of the French revolution of 1789 and its repercussions. The new nation of Mexico began its war for independence with Padre Hidalgo’s Grito in September of 1810. But the struggle for liberty took ten years of bitter, violent, and destructive struggle. As it turned out, the yoke of Spanish colonialism was not easily shed.

The new nation of Mexico inherited legacies of its colonial past as well as the cost of its independence: an uncertain politics, an economy in shambles, a society fractured by class and race, and a vast territory of regional differences, from Alta California and what is today the Southwest to present-day Guatemala—and everything in between. Even in the best of circumstances, managing a new nation after 300 years of colonization would have been a major challenge. Instead, very tough challenges faced Mexico: the development of a stable government; reconstruction of a working economy; the formation of a sense of national identity; the capacity to defend its far-flung borders; and the reconciliation of social and cultural differences.

Secularization of the Missions 1834

The idea of an inland mission in the Spanish period had been abandoned. The appropriation of church properties by the 1833 secularization law divested the Catholic Church of much of its economic power. Expelled from the missions, the natives essentially had to fend for themselves. Many did not return to the villages of their birth. Some became sources of “cheap” labor for employers; others took jobs as vaqueros for rancheros, while many used the skills developed in the missions to be blacksmiths, wagon-makers, and artisans of different sorts. A small number became servants. And still others were driven to rustling cattle and horses, joining natives from the interior.

Originally, the mission had been planned under the Spanish system to last about ten years. At that time, the natives were to be released to parish priests, where land would be turned over to native families for integration into a pueblo or town. By 1829 mission natives had declined to under 4,000; with secularization, the number of ex-mission natives dwindled quickly.

Native Resistance

Natives in the interior had lost much of their caution and trust toward the Spanish-speaking by the early 1800s. The memories of forced abductions, rape, plunder, sickness, corporal punishment and killings were still fresh by 1821. Native resistance became commonplace, as raids on ranchos and settlements increased, facilitated by the use of domesticated horses (another skill learned at the missions that spread quickly over time). The horse made natives highly mobile, and many became expert horsemen; their hit and run tactics created havoc in the ranches and settlements of post-independence Alta California. Distrust, suspicion if not hostility usually marked the interaction between Mexican expeditions and native peoples of the interior

Mexican Expeditions

The decade of the 1830’s saw the Mexican Californios everywhere on the defensive.

After control of California passed from Spain to Mexico in 1822, expeditions into the interior continued, but with a changed purpose. Soldiers were often sent into the interior to recover stolen animals and to punish natives suspected of conducting raids against Mexican communities and ranches. Too often, these forays punished innocent natives that made tensions worse between the Spanish-speaking population and natives.

The Mariposa and Stanislaus Indian wars to the north were among the more violent examples of hostilities that spread into the Valley, making reputations for men like Mariano Vallejo as “Indian fighters”. On the other hand, Estanislao and Cipriano would later become heroes of native resistance. In 1829, the first of three expeditions were sent against Estanislao, a former mission native who led a strong force of runaway neophytes and natives along the Stanislaus River. The first was led by Antonio Soto and the second by José Sánchez, but both were unsuccessful. Only a larger force later under Mariano Vallejo was able to quell the native resistance. The namesake of the Stanislaus River and County, Estanislao fled to Mission San Jose after the defeat, confessed, and received a pardon, as mission authorities did not want to exacerbate tensions with the natives. He remained at Mission San Jose until its secularization and he died in the pueblo of San Jose in 1838.

By 1840, native hostility made inland expeditions too costly and dangerous. Governor Alvarado at the time ordered a military force to patrol the mountain passes to prevent the natives from using them. In 1843 a fort was proposed to be built in Pacheco Pass.

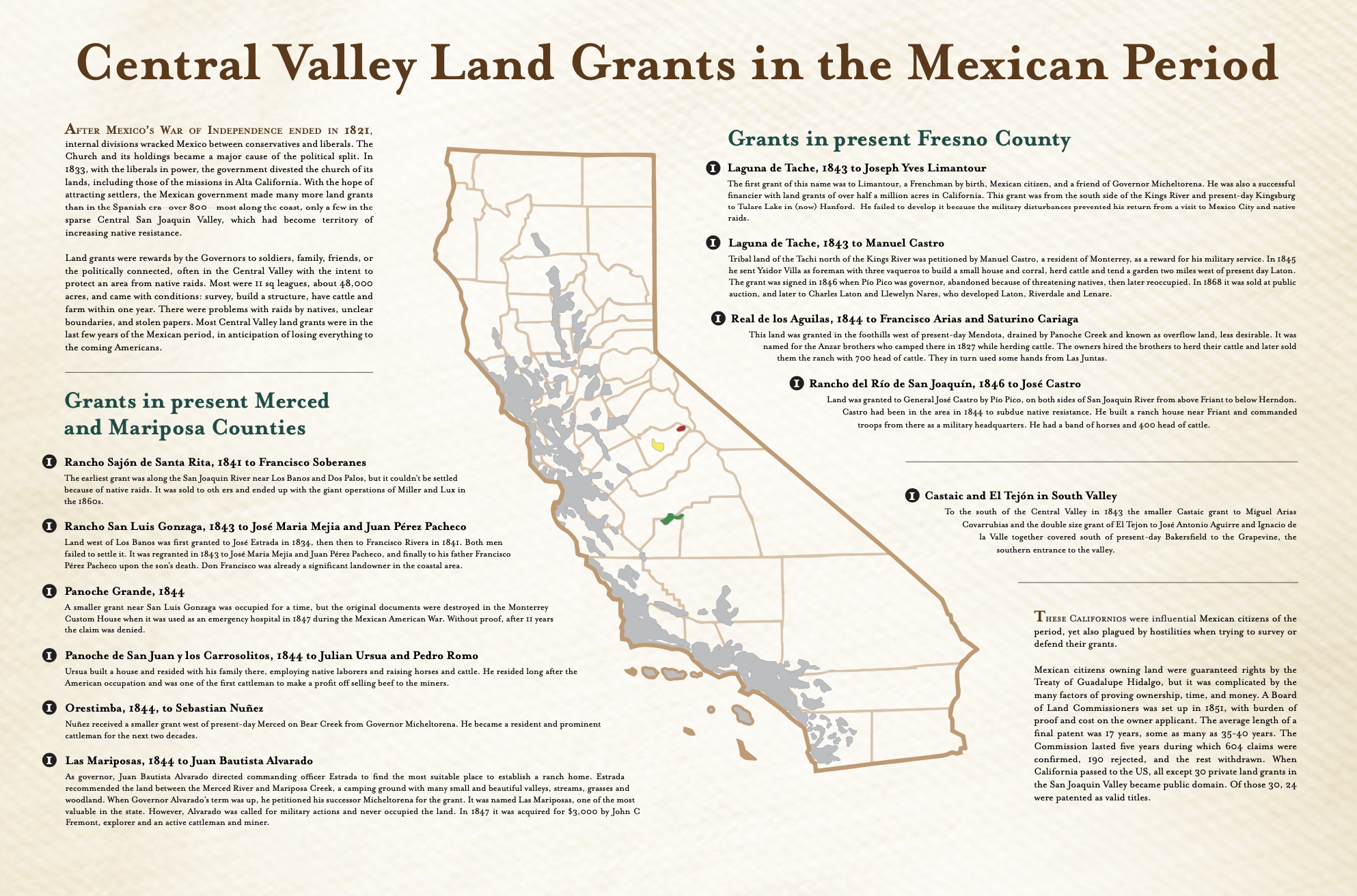

Central Valley Land Grants in the Mexican Period

After Mexico’s War of Independence ended in 1821, internal divisions wracked Mexico between conservatives and liberals. The Church and its holdings became a major cause of the political split. In 1833, with the liberals in power, the government divested the church of its lands, including those of the missions in Alta California. With the hope of attracting settlers, the Mexican government made many more land grants than in the Spanish era—over 800–most along the coast, only a few in the sparse Central San Joaquin Valley, which had become territory of increasing native resistance.

Land grants were rewards by the Governors to soldiers, family, friends, or the politically connected, often in the Central Valley with the intent to protect an area from native raids. Most were 11 sq leagues, about 48,000 acres, and came with conditions: survey, build a structure, have cattle and farm within one year. There were problems with raids by natives, unclear boundaries, and stolen papers. Most Central Valley land grants were in the last few years of the Mexican period, in anticipation of losing everything to the coming Americans.

Grants in present Merced and Mariposa Counties

Rancho Sajón de Santa Rita, 1841 to Francisco Soberanes

The earliest grant was along the San Joaquin River near Los Banos and Dos Palos, but it couldn’t be settled because of native raids. It was sold to others and ended up with the giant operations of Miller and Lux in the 1860s.

Rancho San Luis Gonzaga, 1843 to José Maria Mejia and Juan Pérez Pacheco

Land west of Los Banos was first granted to José Estrada in 1834, then then to Francisco Rivera in 1841. Both men failed to settle it. It was regranted in 1843 to José Maria Mejia and Juan Pérez Pacheco, and finally to his father Francisco Pérez Pacheco upon the son’s death. Don Francisco was already a significant landowner in the coastal area.

Panoche Grande, 1844

A smaller grant near San Luis Gonzaga was occupied for a time, but the original documents were destroyed in the Monterrey Custom House when it was used as an emergency hospital in 1847 during the Mexican American War. Without proof, after 11 years the claim was denied.

Panoche de San Juan y los Carrosolitos, 1844 to Julian Ursua and Pedro Romo

Ursua built a house and resided with his family there, employing native laborers and raising horses and cattle. He resided long after the American occupation and was one of the first cattleman to make a profit off selling beef to the miners.

Orestimba, 1844, to Sebastian Nuñez

Nuñez received a smaller grant west of present-day Merced on Bear Creek from Governor Micheltorena. He became a resident and prominent cattleman for the next two decades.

Las Mariposas, 1844 to Juan Bautista Alvarado

As governor, Juan Bautista Alvarado directed commanding officer Estrada to find the most suitable place to establish a ranch home. Estrada recommended the land between the Merced River and Mariposa Creek, a camping ground with many small and beautiful valleys, streams, grasses and woodland. When Governor Alvarado’s term was up, he petitioned his successor Micheltorena for the grant. It was named Las Mariposas, one of the most valuable in the state. However, Alvarado was called for military actions and never occupied the land. In 1847 it was acquired for $3,000 by John C Fremont, explorer and an active cattleman and miner.

Grants in present Fresno County

Laguna de Tache, 1843 to Joseph Yves Limantour

The first grant of this name was to Limantour, a Frenchman by birth, Mexican citizen, and a friend of Governor Micheltorena. He was also a successful financier with land grants of over half a million acres in California. This grant was from the south side of the Kings River and present-day Kingsburg to Tulare Lake in (now) Hanford. He failed to develop it because the military disturbances prevented his return from a visit to Mexico City and native raids.

Laguna de Tache, 1843 to Manuel Castro

Tribal land of the Tachi north of the Kings River was petitioned by Manuel Castro, a resident of Monterrey, as a reward for his military service. In 1845 he sent Ysidor Villa as foreman with three vaqueros to build a small house and corral, herd cattle and tend a garden two miles west of present day Laton. The grant was signed in 1846 when Pío Pico was governor, abandoned because of threatening natives, then later reoccupied. In 1868 it was sold at public auction, and later to Charles Laton and Llewelyn Nares, who developed Laton, Riverdale and Lenare.

Real de los Aguilas, 1844 to Francisco Arias and Saturino Cariaga

This land was granted in the foothills west of present-day Mendota, drained by Panoche Creek and known as overflow land, less desirable. It was named for the Anzar brothers who camped there in 1827 while herding cattle. The owners hired the brothers to herd their cattle and later sold them the ranch with 700 head of cattle. They in turn used some hands from Las Juntas.

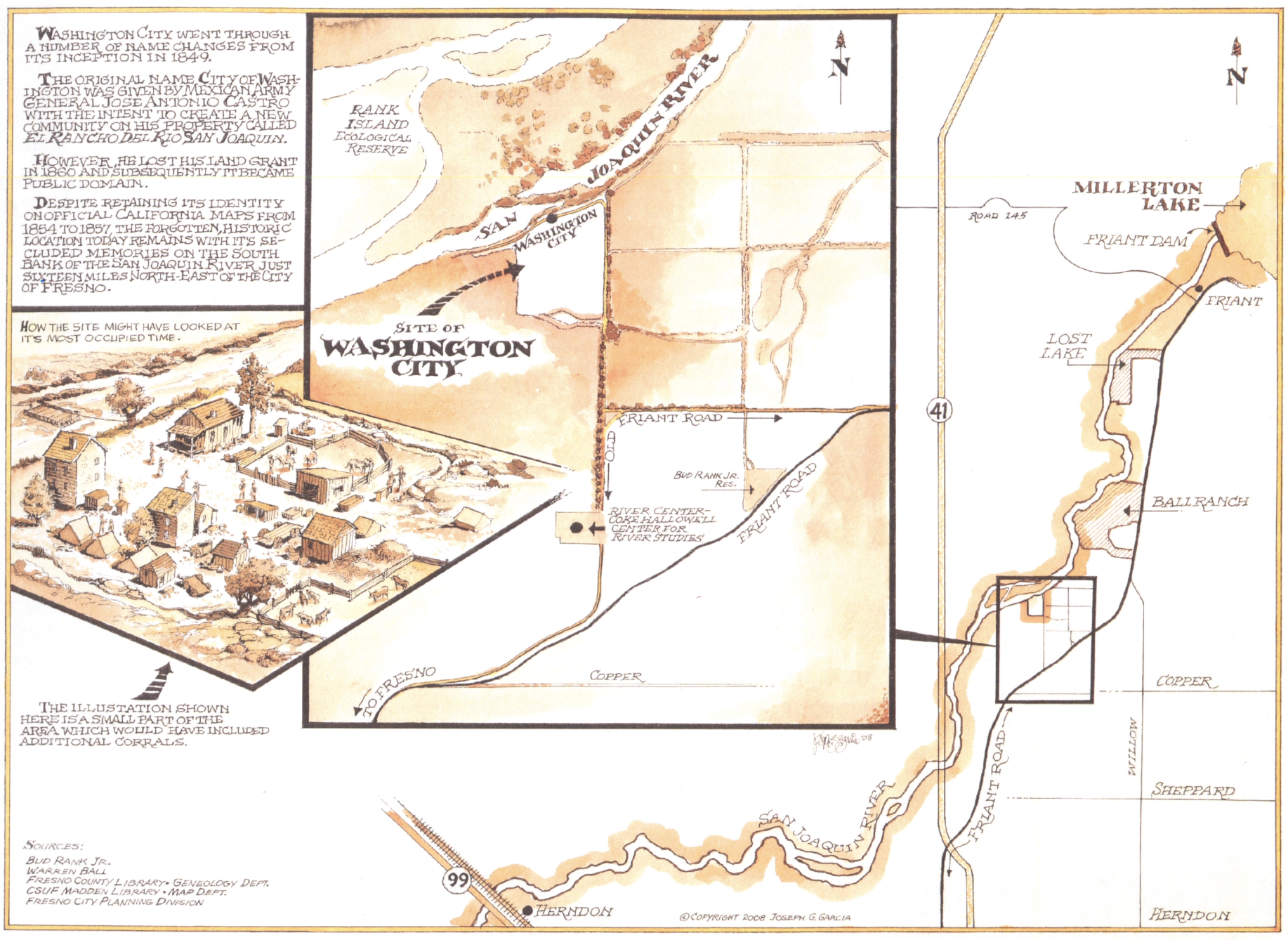

Rancho del Río de San Joaquín, 1846 to José Castro

Land was granted to General José Castro by Pío Pico, on both sides of San Joaquin River from above Friant to below Herndon. Castro had been in the area in 1844 to subdue native resistance. He built a ranch house near Friant and commanded troops from there as a military headquarters. He had a band of horses and 400 head of cattle.

Castaic and El Tejón in South Valley

To the south of the Central Valley in 1843 the smaller Castaic grant to Miguel Arias Covarrubias and the double size grant of El Tejon to José Antonio Aguirre and Ignacio de la Valle together covered south of present-day Bakersfield to the Grapevine, the southern entrance to the valley. These Californios were influential Mexican citizens of the period, yet also plagued by hostilities when trying to survey or defend their grants.

More on Grants

Mexican citizens owning land were guaranteed rights by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, but it was complicated by the many factors of proving ownership, time, and money. A Board of Land Commissioners was set up in 1851, with burden of proof and cost on the owner applicant. The average length of a final patent was 17 years, some as many as 35-40 years. The Commission lasted five years during which 604 claims were confirmed, 190 rejected, and the rest withdrawn. When California passed to the US, all except 30 private land grants in the San Joaquin Valley became public domain. Of those 30, 24 were patented as valid titles.

Although popularly referred to as Spanish Land grants, Spanish concessions (about 25 from 1784-1821) were little more than grazing permits given to retired soldiers as an inducement for them to remain in the frontier. The concessions reverted to the crown upon the death of the recipient. Many were patented later under Mexican laws.

The Mexican government encouraged settlement by issuing much larger land grants (270 from 1833-1846) to native born and naturalized citizens, approx. 14 sq miles or 4,429 acres, with unencumbered ownership rights. Legislation provided half of the mission lands to natives and half to the government, consisting of about 200 families, friends and political allies–rancho aristocracy. That requirement was quickly ignored by Californios. The 1824 Mexican Colony Law rules for petitioning land grants, was codified in 1828, giving Governors the power to grant (frequently to friends.)

Over half of the grants were filed in the last seven years of Mexican rule, including those in the valley. A significant number were given to non-Mexicans and some were held by women, making them powerful targets for marriage. The rapid increase in claims for land grants coincided with the rise in importance of the hide and tallow trade and the expectation of land appreciation following American occupation. Lack of markets meant extensive use of the land, for livestock, so it would take a huge increase in population to make the valley’s land grants viable.

Don Francisco Pacheco and the Rancho San Luis Gonzaga Land Grant

The land that became Rancho San Luis Gonzaga was originally granted in 1834 to José Estrada, then regranted in 1841 to Francisco Rivera… (read more)

The Castro Land Grant

In 1844 Governor Manuel Micheltorena charged Lieutenant Colonel José Antonio Castro with leading an expedition into the Central Valley to establish a headquarters… (read more)

Los Californios

Few people migrated from Mexico to the frontier. The long, difficult, and dangerous overland trail to Alta California discouraged settlers. The coastal areas received most of the government’s land grants, only a handful were made in the valley. Valley settlers would have lived a very isolated, lonely life, with only an occasional visit from those on the Camino Viejo to alleviate the monotony of a remote, insecure frontier existence. Voyages from Mexico were erratic, lengthy and hazardous, making them an uninviting way to reach Alta California. The population continued to hug the coast, and very few ventured into the interior except the vaqueros who periodically conducted a rodeo of feral cattle and wild horses.

Between the Spanish and American occupations of Alta California the short term of 27 years under Mexican rule was characterized by various loyalties to Mexico and attraction to the approaching U.S. Complicating the situation was the increasing presence of the mountain men, crossing to California as scouts, trappers and sometimes opportunists.

Only a few sparsely populated Spanish and Mexican settlements had developed in the interior:

Pueblo de San Emedio south of Bakersfield thought to be oldest, and Poso Chana, East of Coalinga on the site of an old Yokuts village. Las Juntas, developed near present day Mendota. All three of the villages were populated in the main by AWOL Spanish or Mexican soldiers, plus their mestizo families,

Life in the Central Valley during this period was one of increasing native resistance. Many of the Mexican military men of the time gained offices and land grants for their efforts in combating the native resistance. But the romanticized idyllic life of the Californios and Ranchos was not possible and may have been an attempt by the losing Mexican population to glorify their heritage against the encroachment of the Yankee Americanos. If that fantasy existed at all, it was a coastal phenomenon.

Few native Spaniards were in Mexico by now, as well as in the Valley, after generations of intermarrying or mating with native populations. They referred to themselves as “Californios” and could not have been many–one generation, maybe two. Most of them were on the Coast, but those in the Valley had a more complex link with California natives and names that entered their vocabulary. Mexican artisans, vaqueros and majordomos of ranchos were the backbone of settlements. Gente de razón had government positions or controlled the military and the ranchos. They were not interested in farming, yet Mexican settlers introduced the zanja system of irrigation, canals fed by gravity flow from a dam.

California had a more independent spirit, but still was subject to class and status. Spanish Franciscans, officials and some soldiers, were gente de razón. Mexican soldiers, artisans, colonists, and cholos had lower status, and the “neophytes” (the native converts) were essentially slaves. Spaniards and Mexicans intermarried or mated by class. Unconverted natives away from mission areas and in the Valley were pretty much left alone. In Mexicanized California, Yankee and European fur trappers did not blend into society. Mexican vaqueros gained a positive reputation for their skills and retired sailing captains earned acceptance. Mexican California women were somewhat more favorably disposed to Yankee men and by the end of the Mexican period, were prizes for Yankee men in gaining access to Mexican land grants.

BY 1848 THE VALLEY’S POPULATION

By 1846 Mexicans of substance ruled California rancho life, 46 individuals in power, with Mariano Vallejo the largest landholder among them. Native population in all of California had shrunk to less than 100,000 plus a minority of 14,000 which included mostly those of Hispanic descent and an estimated 2,500 “foreigners or whites. Most of those had immigrated from US since 1840, the beginning of a great influx.

The estimated population of the valley included only an estimated 30 European Spaniards. All other Spanish speaking, of 1,066, including soldiers, settlers and artisans born in Mexico. By 1848 only 1,500-2,000 were left. In all of California were 7,500, the majority mixed Spanish and native ancestry.

The landowners of the rancheros in the Valley could be counted and named. The native population was decimated or working on ranches. Those Californios, maybe 13,000 in a population of 100,000 in 1849.

Profiles in the Mexican Period

The last Governors under Mexican rule:

Juan Bautista Alvarado 1836-1842

Manuel Micheltorena 1842-1845

Pío Pico 1845-1846

The governors and military leaders (some both) were key players in the Mexican period, a total of thirteen governors in a turnover during 27 years from the seat of Alta California in Monterrey. The last three played a role in the Central Valley through land grants. Many Californios were conflicted in this period with loyalty to distant Mexico and the advance of the Yankee Americanos. Micheltorena said the “war disturbed our otherwise idle lifestyle.” Pío Pico referred to the people as Californios, not Mexicans. Pico’s power ceased on July 7, 1846, when a US Flag was raised over Castro House in Monterrey.

As Governor, Juan Bautista Alvarado directed commanding officer Estrada to find the most suitable place to establish a ranch home. Estrada recommended the land between the Merced River and Mariposa Creek, a camping ground with many small and beautiful valleys, streams, grasses, and woodland. When Governor Alvarado’s term was up, he petitioned his successor Micheltorena for the grant. It was named Las Mariposas, one of the most valuable in the state. However, Alvarado was called for military actions and never occupied the land. John Fremont acquired it in 1847 for $3,000.

Los Soldados

In 1825-1828 expeditions from San Juan Bautista led by José Dolores Pico and Sebastian Rodriguez entered the valley to successfully capture and intimidate the escaping neophytes and recapture stolen horses. In 1829 three expeditions against Estanislao, first two by Antonio Soto and José Sánchez and the third by Mariano Vallejo along the Stanislaus and Tuolumne Rivers. Finally, Vallejo from Sacramento was sent and successful. Others awarded land grants for their military efforts were unable to hold on to the land they were awarded and did not become successful ranchers.

Los Rancheros

Those who were able to establish cattle ranches became the most successful and influential. They turned the focus of the cattle industry from hide and tallow to feeding the exploding population of the later miners and settlers. They included Ursua, the Anzar Brothers, Sebastian Nuñez, and Don Pacheco. The Mexican American War drained many of the rancheros for defense.

In the southern end of the Valley, Covarrubias was one of three San Joaquin Valley rancheros active in framing of the first California state constitution in 1850. The Covarrubias land was El Tejon Castaic to grapevine, Bakersfield area. He had two grandsons who became internationally recognized, including artist and caricaturist Miguel Covarrubias.

Mountain Men

Yankees and Europeans Invade and Scout the Valley 1827-1834

The Northern territories were isolated. with increasing Russian, French and American incursions. Jebediah Smith, one of the first fur trappers and Yankee traders, was allowed to travel the Valley. He lost most of his men or left them trapping. He sold $3,000 in furs out of the San Joaquin Valley. A second Smith from Kentucky, with a peg leg, became friend to the Indians, taught them to steal horses and sell them. Kit Carson, a great grandson of Daniel Boone, also became known for killing Indians. Ewing Young and Peter Lebec of the Hudson Bay Company established a permanent camp near Stockton with many French men—French Camp. In 1833 Joseph Walker of Tennessee was overwhelmed by Yosemite and turned back. In 1845 an exploring party of Walker, Owens, Kern, and Fremont described the valley. These singular incursions were invaders. John Fremont was a key scout of the valley.

American, British, Scottish, German, and French adventurers prior to 1848 officially were Mexican and some of them married daughters of gente de razón, eligible for land grants and to engage in trade. By the mid-1840s Americanos began to increase dramatically and allegiances underwent changes.

Natives

Meanwhile, the native population declined further, from disease and the loss of ancestral sources of food and water from the environmental damage of invasive plants and animals that multiplied in the fertile land of the valley. Mexican rule gave Indians equal status in the constitution as part of freeing slavery. From the beginning to the end of the Mexican period estimated native population in California went from 310,000 to 100,000. 72,000 Indians passed to American Sovereignty.

The Mexicans considered themselves culturally (but not racially) superior and sought to incorporate natives as laborers. Yet they were economically exploited and militarily coerced, regarded as human beings who could only achieve status by adopting language, culture and religion.

By 1829 the native population is estimated to have experienced a catastrophic decline from 15,000 to 4,500. By 1847, with the dissolution of the missions, they had disappeared into pueblos, villages, and ranchos. Pueblo Indians of the southwest, those with villages, monogamistic, and irrigated farming were most likely to survive the colonization and adapt to mission life. Nomadic Indians warlike, were masters of the Southwest in 1848. The Indian resistance was the greatest factor protecting the borderlands from both Spanish and Mexican conquest. (Homeland Security Poster).

Mestizos

Many were mixed, mestijos, or Mexicans. The people not born in Spain or Mexico, but California during this time referred to themselves as “Californios” and could not have been many–one generation, maybe two. Most of them were on the coast, not in the valley, but those in the valley had a more complex link with California natives. Mexican artisans, vaqueros and major domos of ranchos, craftsmen and pobladores of pueblos were the backbone of settlement. Gente de razón had government positions, or controlled the military and the ranchos, not interested in farming. Mexican settlers had already introduced a zanja system of irrigation, canals fed by gravity flow from a dam.

California had a more independent spirit, but still was subject to class and status. Spanish Franciscans, officials, and some soldiers, were gente de razon. Mexican soldiers, artisans, colonists, cholos were poor white trash. Neophytes, the native converts, slaves. Spaniards and Mexicans intermarried or mated by class. In this rancho period, natives were pretty much used as slaves or peons for wealthy patrons. Those away from mission areas and in the valley were pretty much left alone. In Mexicanized California, Yankee and European fur trappers did not blend into society. Mexican vaqueros gained a positive reputation for their skills and retired sailing captains earned acceptance. Mexican California women were somewhat more favorably disposed to Yankee men and by the end of the Mexican period, were prizes for Yankee men in gaining access to their Mexican land grants, for in the Mexican system, women could inherit land.

The Mexican American War 1846-1848

The War cut short the Mexican rule of Alta California

The U.S. had long coveted Mexico’s western territory. President John Quincy Adams tried to buy Texas in 1828. In 1835 President Andrew Jackson offered to buy San Francisco Bay. In 1845 President Polk sent John Slidell to buy Mexico for up to 25 million dollars–Mexico refused the offer. In his inaugural address, he stressed that the world had nothing to fear from the “military ambition in our government.” Fifteen months later, Polk took the country into a war with its neighbor, determined to obtain Alta California and he won. In sum, it was a one-sided war. Mexico’s weaknesses, despite its resolute resistance, led to its defeat in 1848.

Among the politically influential Californios, some sided with the Americans, others with Mexico.

The Mexican American War did not have an immediate effect on the central valley. It splintered the Californios statewide and set the stage for the animosity and hatred that persisted well into the next Early American era.

We didn’t cross the border…the border crossed us.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, 1848

The Treaty established a border between the two countries, serving the expansion of U.S., while Mexico lost roughly half of its territory.

During this Mexican period, Mexico itself had been weakened by its revolution and could no more hold on to, supply or colonize California than the Spanish government had been able to do. The last desperate and confusing years of Mexican rule saw increasingly rapid distribution of land and ways of cheating the owners out of it. It seemed a time when plots and politics were determining who would succeed at taking over California, and the interior valley was more a bystander in that play than a participant. The ultimate winner was the United States and the next period of the gold rush assured that the Yankee occupiers would pour in and overwhelm. The irony is that the Spanish conquistadores had been seeking glory, god and gold. Gabriela Moraga made 46 expeditions to the interior, some near the Mother Lode. Gold was here in the valley all along.

Manuel Gonzalez, Mexican California