1849-1900

Early American CaliforniaGOLD AND GRINGOS

Early American Transformation of the Valley 1848-1900

The California gold rush triggered a series of interrelated changes that transformed the central valley by the turn of the 20th century, notably: the rapid increase in population; the impact of the railroad; the development of intensive agriculture; the fast expansion of irrigation works; the growing demand for labor; and the spread of race-based ideas and policies, which led to a stratified, segregated society. In the midst of these shifts, clusters of Mexicans (colonias) gradually emerged, a prelude to the coming wave of newcomers after 1900.

News of the discovery of gold in 1848 led to a human tidal wave from various parts of the world. Among the first to arrive were Mexican, Peruvian, and Chilean miners; their expertise made them generally more successful than those without such skills, especially most American would-be prospectors, who usually entered the “diggings” later due to the distance to get to California. Competition for productive claims quickly intensified, and resentment mounted toward those “foreigners,” whose relative success led to racially-charged efforts to force them out of gold country, such as the discriminatory Foreign Miners Tax of 1850, or if necessary, by violence. The biased judicial system offered scant help to the “foreigners,” including Spanish-speaking miners (often referred to by the derogatory term, “greasers”); in the face of such injustices, most of them left for their homelands or the old coastal towns. Their departure deprived the valley of potential businessmen, land owners, professionals and the like, given the opportunities afforded by the budding economy of the valley in the wake of the gold rush.

Some, however, resorted to social banditry, a form of resistance found in the exploits of Joaquin Murrieta, for instance, whose “gang” ranged over the valley, robbing coaches and their passengers of their valuables. California Historical Landmark #344, near Coalinga, is the site where in 1853 Murrieta was allegedly killed in a shootout with lawmen. Nonetheless, his resistance remains the inspiration for the trail ride of Mexican charros on the westside of the valley that has taken place annually since 1977.

The end of gold rush had nevertheless left the state with a sizable population that was quickly augmented by continuing migration from other parts of country. Land speculation and the entry of the railroad combined to accelerate the size of valley towns and cities by the 1870s, as much of their growth reflected the boom in agricultural production toward expansive markets, from figs and oranges to peaches and raisins—spurring a voracious demand for labor. Farmers in particular turned to Asian immigrant workers, Chinese, Japanese, and Sikhs; but they were subjected to a series of racist immigration policy restrictions that over time dwindled their availability. European immigrants as well as U.S.-born migrants were also tried, but they proved insufficient in number and/or in productivity. African Americans also were recruited, yet again they were too few to fill the need, as irrigated farming spread from one end of the valley to the other. By 1890, for example, according to the agricultural census of that year, 9,000 workers were necessary just to tend to the vineyards of Fresno County.

Consequently, employers increasingly looked south for a source of labor, as the number of Asian immigrant workers fell victim to racially-motivated legislation; still later federal policies also restricted the entry of southern and eastern European immigrants. By 1900, drawn by the possibilities of employment, Mexican-born people began to appear in the census of 1900 in valley towns, such as the Morales, Romero, and Salazar families of Visalia’s ward #4; the latter headed by Jesus Salazar, who became a famed saddle-maker.

Yet, for most people at the time, the historic connection to the Mexican and Spanish past of el valle del rio san joaquin went unheralded and little understood; only the names of certain places retained the residue of that time. But a decisive period in that connection was in the making, which would irrevocably change the central valley.

By Dr. Alex Saragoza

FOREIGNERS IN THEIR NATIVE LAND

The Californios began the next period with what they thought were guarantees and an intent to participate in the new California politically and economically. California’s first constitution was written in English and Spanish with some participation of the Californios. In 1849, 13% of the population of California were Californios, almost all on the coast.

In this era of transformation, the Valley now became a focus. Before the Treaty was signed, the Gold Rush and the prospect of land and new beginnings created a Yankee invasion that outnumbered Californios ten to one, bringing devastating results on all the former inhabitants, mestizos and natives. The pattern of relationships was set. They literally became “foreigners in their native land.”

AMERICAN GENOCIDE

As to what would happen to the original population, already devastated by the Spanish and Mexican occupations, it was clear as the words of Peter Barnett, California’s first American governor in 1851:

“That a war of extermination will continue to be waged between the two races until the Indian race becomes extinct, must be expected; while we cannot anticipate this result with but painful regret, the inevitable destiny of the race is beyond the power and wisdom of man to avert.”

The governor during this time placed a bounty on the scalp of any native killed by white settlers. When California became the property of the US in 1848 as a spoil of the Mexican American War and then a state in 1850, it became an imperative to made room for the new “settlers” and make claim on any gold on traditional tribal lands. Natives were in the way, seen as threats or nuisances to be wiped out, displaced, decimated. That could apply also to mestizos, part Mexican, part native.

“By demonstrating that the state would not punish Indian killers, but instead reward them, militia expeditions helped inspire vigilantes… and the US Army also joined in the killing. An estimated 100,000 died during the first two years of the Gold Rush. By 1873 only 30,000 remained of around 150,000, and the state had spent about $1.7 million to make it happen.” Madley, American Genocide.

During the periods of Spanish and Mexican occupation, California’s estimated native populations fell from 300,000 to 150,000, with more than half of the loss at or near the coastal missions. Under US rule 1846-1870 their numbers plunged as low as 30,000. By 1880 census takers recorded just 16,277 California natives. Knights Ferry became a refuge and melting pot for those vanished in the wars of Tuolumne, Stanislaus, and lower Calaveras. Those tribes north of the San Joaquin River were decimated first by missionaries, massacres, malaria, and finally by gunpower and the Gold Rush.

“They made choices about their futures based on their sense of history and their standards of practice, accommodating, working, fighting, hiding out—in a word, surviving—they were the seeds for today’s California Indian population. Despite the odds, California has the US largest Native American population, home to 109 federally recognized tribes.” Madley, American Genocide.

In the valley some native tribes have established casinos, adding to our common vocabulary of Spanish and English names those of Chuchansi, Mono, Tachi.

GOLD & GRINGOS

At almost the same time the United States took over Mexico’s northern lands in 1848, news of the discovery of gold went out from Sacramento. Deposits of gold may have been discovered earlier, in 1839 along the coast, by natives along valley riverbeds, by Francisco López in Santa Feliciana Canyon as early as 1842 with a cry of ¡Chispa! (spark) as he dug among onions.

Within a year a flood of gold seekers from everywhere outnumbered 10 to 1 the small Mexican Californio population that existed. The first miners to arrive were from Sonora in northern Mexico and from Chile, experienced in mining and successful in the beginning. Next came Chinese seeking the “Golden Mountain” and by 1849 the beginning of the Yankee ‘49ers.

“Gold conveyed an irresistible magic, visions of wealth, luxury, splendor. Consider its impact on 19th century people. Farmers dropped plows, teachers fled classrooms, husbands left families, wives abandoned mates, clerks gave up books, doctors exchanged bags for pick and shovel. It touched off an unprecedented movement of people to California, as thousands trekked across the nation by the Oregon or Santa Fe trails, or came by ship around South America, some up to the Valley through the Tejon Pass and following the eastern foothills of the Sierra to avoid the marshes and tules.”

Alex Saragoza in Land Between Rivers.

The first mines were in north and central Sierra. Soon the southern mines developed in the Central Valley along the hills of the tributaries of the San Joaquin River, in the foothills from the Mokelumne River to Kern, in Millerton, Dry Creek, Hornitos, Kings River, and Hanford.

FOREIGN MINERS TAX

The initial onslaught hit the “diggings” where gold was found more easily at first by those with the experience and skills. That phase soon ended as competition intensified and resentment built toward “foreigners” whose success led to efforts to push them out of the diggings, often by violence The camps were segregated and developed their own laws in the absence of authorities. Whatever biased judicial system there was offered scant help to the “greasers,” the derogatory term for Spanish speaking miners.

Miners could make an average of $1/day, but the California Foreign Miners License tax legislation of 1850 was an attempt to drive out the “foreigners” (any Mexican, Chilean, Chinese or native). Charging $20 a month for the fee to mine effectively drove away many before it was repealed in 1851. Businesses affected by the loss of miners as customers opposed it–and “maybe” it violated the Treaty.

RACISM AND PREJUDICE IN THE MINES

Mexicans who poured into California during this period were still inflamed with anti-American prejudices from the Mexican War. Americans also regarded Mexicans suspiciously and with contempt. Vigilante law was widespread with no effective government from 1846-1850. Two thirds of the miners in the northern regions of Calaveras, Tuolumne and Mariposa County were driven out by the Yankees, some 15,000. It was worse in the southern mines. Up to 1860 Mexicans were the majority in all the counties of the southern mines. By 1862 many left. By 1870 they had disappeared. Threats of violence, vigilantes, robbery, fraud, and lynching pushed most of the Mexicans to Southern California and old coastal towns and Chileans to the north. Others and their native brothers fled to the foothills, hired out to rancheros, or established small settlements. Some became bandits, even some of the gringos.

THE GOLD RUSH SET AN UNFORTUNATE PATTERN OF RELATIONSHIPS

Some Yankees did make their fortune, like Levi Strauss who created and sold his “jeans” to the miners or Leland Stanford who created businesses in San Francisco, became governor in 1861, senator in 1885 and a railroad baron. A few rancheros sold cattle to meet the demand for meat. For most former mexicanos it was a loss of potential entrepreneurs, investors, businessmen, landowners.

California’s population in this period was overwhelmingly male. The few women recruited or indentured as laundresses or in the gambling houses were seeking their share of the gold, many from Latin American seaports where females outnumbered men, “gold diggers.” In contrast, many Sonorans came with families to settle and returned to Mexico in the winter. Early on there were also violent clashes of miners and landowners, many miners giving up and squatting on ranchero lands.

The average output from the gold fields 1850-1865 was $50 million per year, down to $10-$20 million after 1865, then industrialized in 1910. Land, oil, water became the new gold.

Reflecting on decades past, the Spaniards, who left in 1820, were 28 years from the discovery and the Mexicans only a month. In the long run the Gold Rush era was a mixed blessing, a product of mass hysteria that set the tone and state of mind in which greed predominated and disorder and violence were too frequent. Most important for this camino, the Gold Rush set an unfortunate pattern of relationship between Mexicans and Americans.

LAND GRANTS & LAND GRABS

The rancheros with their Mexican land grants did not fare much better than the Mexican miners. By 1846 lands and cattle had passed into the hands of private landowners who collectively owned 1/8 of the state in units from 4,500-50,000 acres. By the time of the Treaty in 1848 (with its guarantee of ownership) 200 Mexican families owned 14 million acres–something that was seen as undemocratic, enviable, greedy, resented, and most of all coveted. Over half of the grants had been filed in the last seven years of Mexican rule, including those in the valley. A significant number were given to non-Mexicans, and some were held by women (who could own and inherit land in the former Mexican system), making them powerful targets for marriage–marry a daughter of one of the big landowners was a quieter way to clean her family of its assets than to lend money to the ‘old man.’

RANCHEROS BECAME LAND RICH AND CASH-POOR

The United States had guaranteed in the Treaty existing rights of land. To settle the complex problem, the Land Act of 1851 established a Land Commission to adjudicate claims from 1851-1856. Some Mexican land grants had unmet conditions, vague or overlapping boundaries, or faulty legal titles. Fraudulent land claims cast suspicion on valid ones. Spanish speaking rancheros required English speaking lawyers to defend them in an American court system and sometimes took their fees in portions of land. Some co-signed loans for family or friends they could not replay or sold to land speculators. Some cases took years to defend. Many lost their claims through delays, eaten away by increased taxes and lawyer fees, or unable to document proof of ownership. Although eventually two thirds of the claims were upheld, it took years in costly appeals and by then the land value was dramatically decreased or sold off. Of course, there was also fraud.

“It is the conquered who are humbled before the conqueror asking for his protection, while enjoying what little their misfortune has left them. It is those who have been sold like sheep—it is those who were abandoned by Mexico. They do not understand the prevalent language of their native soil. They are foreigners in their own land. I have seen seventy- and sixty-year-olds cry like children because they had been uprooted from the lands of their fathers. They have been humiliated and insulted. they have been refused the privilege of taking water from their own wells. They have been denied the privilege of cutting their own firewood.” Pablo de la Guerra, 1856, Speech to the CA Senate

Antonio Maria Pico and forty others in 1859 signed a petition to US Senate and House, saying they had been “compelled to sell little by little by little.”

SQUATTERS BEGAN TO OCCUPY THE LAND GRANTS

Discouraged miners had begun to occupy Spanish and Mexican land grants in the Central Valley by 1850—squatters. In 1841, the first Squatters Act allowed squatters to preempt other claims and pay $1.25 per acre for up to 160 acres, whittling away some lands of the ranchos. In 1862 the first Federal Homestead Act made the land available to homesteaders if it was rejected by land grant claims.

BY 1870 ALMOST ALL LAND GRANTS HAD BEEN TAKEN OVER BY AMERICANS

Despite the obstacles, the Commission did approve 553 claims totaling some 8,850, 000 acres. The 197 rejected grantees had failed to adequately document their claim, were withdrawn, or were deemed fraud. By the 1890s the ranchero class of the Californios was destroyed. Some were able to hold on to remnants of their original massive land grants, most were not.

The Castro land grant in Fresno was not much defended and gradually broken up. Don Pacheco was one of the few valley grant owners to keep his claim, ultimately partially taken from the family in the next century for the California aqueduct. Looking further south, by 1860 four vast southern grants were absorbed into Rancho Tejon.

A SHIFT FROM CATTLEMEN TO FARMERS

The rapid increase in claims for land grants had coincided with the rise in importance of the hide and tallow trade and the expectation that land values would increase following American occupation. The rancho system had depended on native labor and large tracts of land for livestock. Many became prosperous selling beef at increased prices, especially to the miners. The flood of 1861, followed by two years of drought 1862-1864, devastated the industry and wiped out many ranchers. It would take a huge increase in population to remake the valley for viable agricultural production–which happened eventually via the Gold Rush.

Spanish speaking people played important, but often unrecognized roles in the early years of California history, for the newcomers were only dimly aware of California’s Hispanic past.

Vaqueros and Bandidos

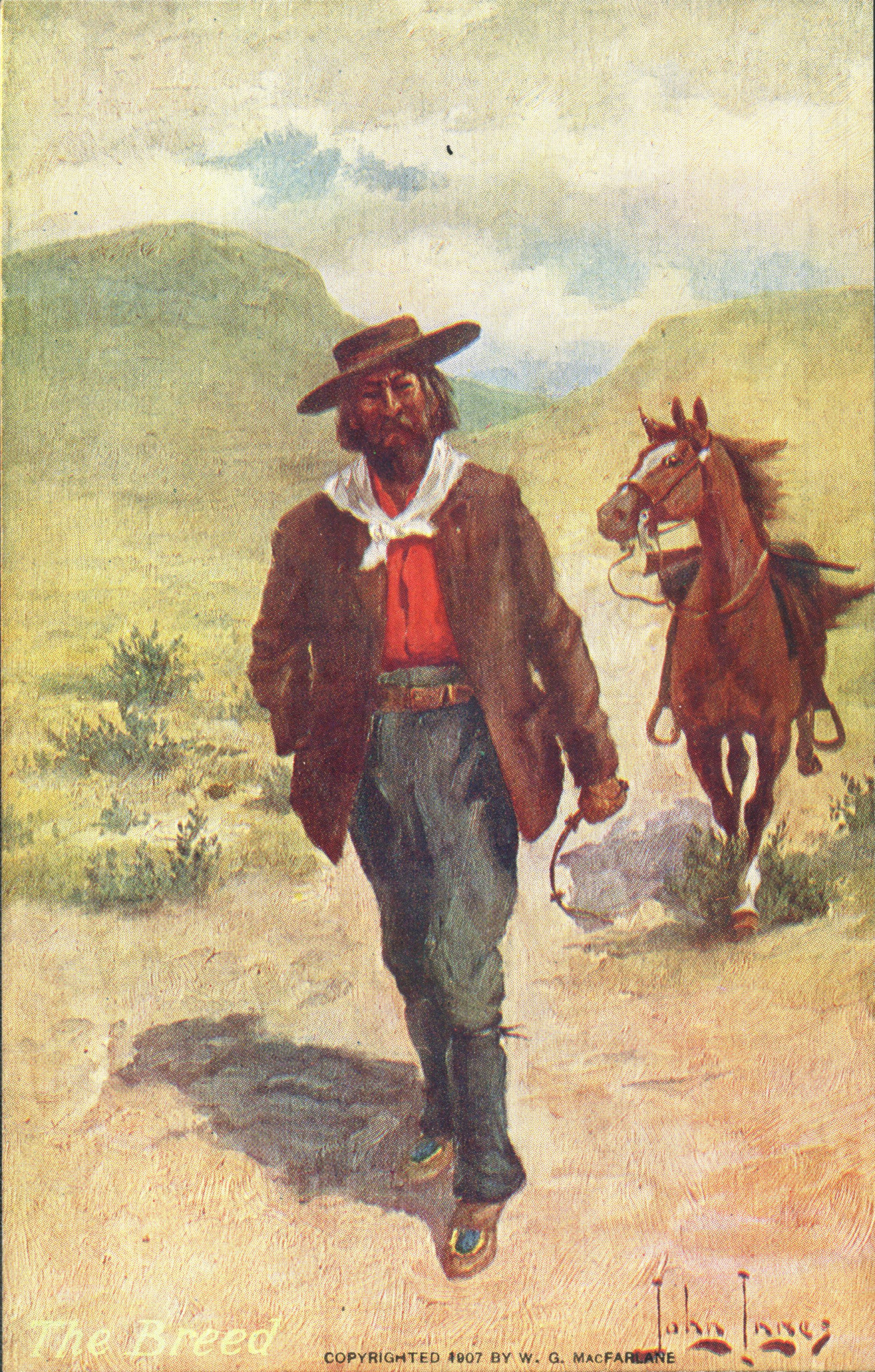

For all the prejudice and injustices of this period, although Mexicans were hated and denigrated, they were respected and prized as vaqueros. The horsemanship and traditions that were carried from Spain to Mexico and Alta California resulted in the transfer of the vaquero culture to the cowboy one. Even the words transferred: vaquero to buckaroo (cowboy), lariata to lariat, rodeo to rodeo.

The valley functioned as a corral, filled with wild horses to be captured and branded. Mexicans and artisans in this period with the skills of the vaqueros found a place in the valley, herding and driving cattle, selling beef to the growing and hungry population. Ursua and Castro were among the earliest valley cattle barons.

The west side of the valley and especially areas around the Tulare region became vaquero country, from the holding stations for captured horses in Arroyo Cantua to the Visalia Saddle shop as the most sought source for vaquero needs.

JESUS SALAZAR AND THE VISALIA SADDLE SHOP

Jesús Salazar, 1836-1903, invented a version of the Mexican saddle prized by the valley’s vaqueros and especially known for its large flat round Mexican style horn. In 1868 Juan Martarel opened the Visalia Saddle Shop, serving the valley’s vaqueros. Martarel was trained in El Salvador and came to Hornitos in the late 1850s. He had two Mexican employees and was bought out in 1870 by Walker and Shuman.

Words of the historic plaque

LAS JUNTAS

Pueblo de las Juntas (junction or meeting place) was also known as Fresno for the ash trees that grew on the riverbank near Mendota. It seemed to be known in the earliest times as a place Spanish soldiers raided for mission natives, moving them by force to Mission San Juan Bautista. In this eras it became known as another meeting place, the rendezvous and refuge for adventurers and bandits, with a reputation for horse stealing, gambling, drinking and murder. In 1879 the town was purchased by the San Joaquin and Kings River Canal Company and the remaining 200 persons moved to Firebaugh, where some of them found jobs with the company and others paid $1 to purchase land.

Bandidos

From the beginning of American occupation, establishing law and order took time. The military presence that the Spanish and Mexican governments had conducted from the coastal seats of power left a gap until the US justice system (as it was) gradually took over. For all who grew up watching western movies, the familiar but stereotypical scenes of “cowboys and indians,” of lawlessness in frontier towns, of saloons and jails as the center of focus–this could describe many valley towns of this period, including Fresno and Visalia. Law and order were a localized force, mixed with vigilante justice–or none

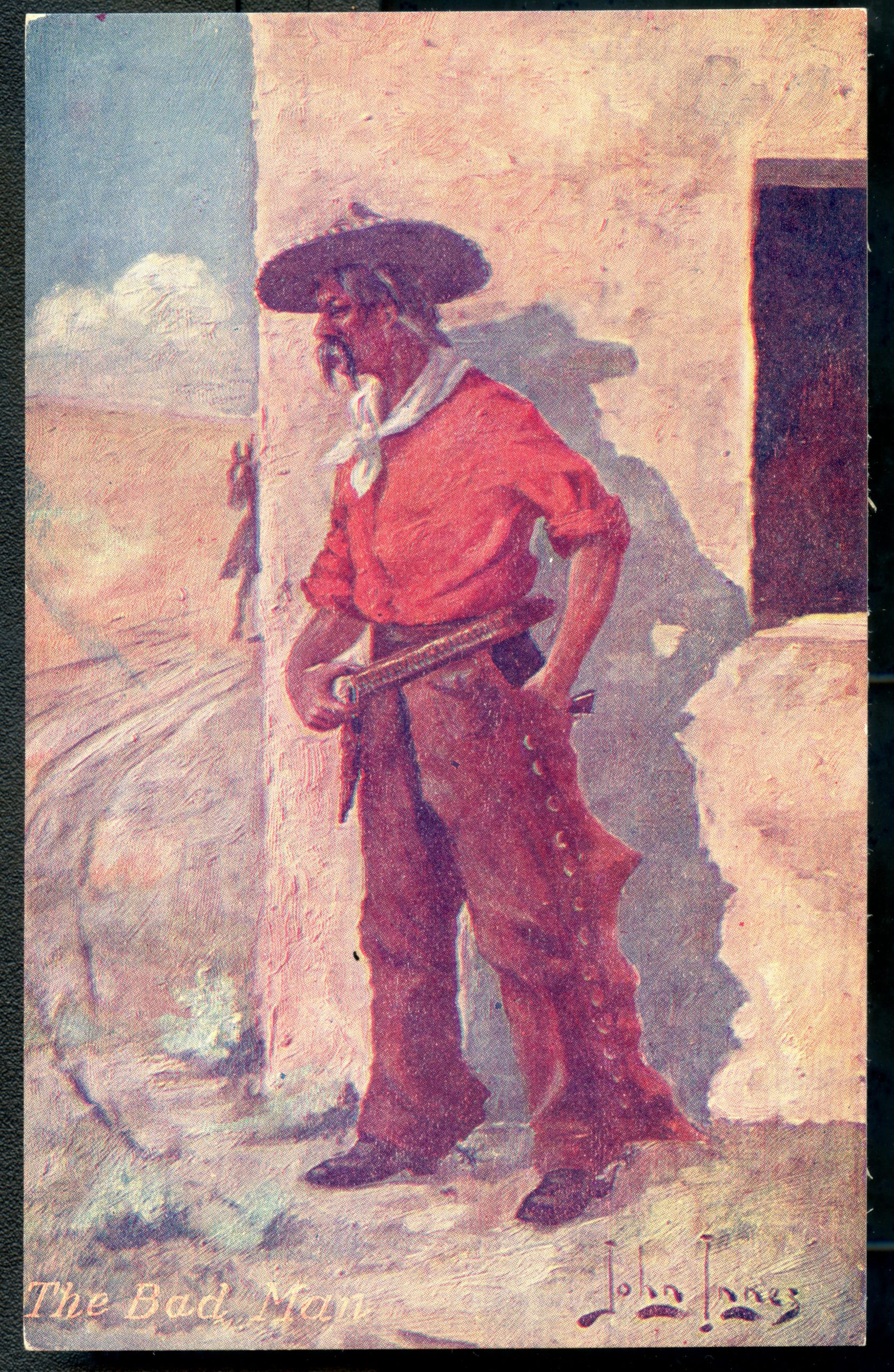

Mexican mestizos and some gringos, driven from the mines and with few avenues left open, turned to banditry in the outlaw areas of the valley, mostly stealing cattle or horses. When stages and trains began traversing the valley, robberies were the danger of passage. Bandits were particularly prevalent in the period from 1852 to 1864 and for the sensational press and fiction of the times, their exploits fed a curious nation. In the minds of those consuming the popular tales and exaggerations of the times. Black Bart, Billy the Kid, Daniel Boone, Davy Crockett became legends in a similar way.

Among the bandits, Joaquín Murrieta and Tiburcio Vasquez stand out, one for the mythological and fictional levels his story reached, and the other well documented. Both are by some labeled “social bandits,” a term for peasant outlaws regarded by the state as criminals, but remaining within the peasant society and considered heroes, champions, avengers, and fighters for justice. In that view they are admired, helped, and supported. For a while these bandit avengers terrorized California until they were caught and killed. As a proud Mexican people just conquered and mistreated, “rebels” and “freedom fighters” could be another term considered.

However, most of the landed Californios left in the period of the bandits would have detested the lawlessness.

“Listen to the various accounts of the life of Joaquín Murrieta and you will believe that something terrible and sad happened in California once upon a time…The truth is—we are all bandits. We’ve stolen California from the Mexicans and they stole it from the Indians. We can deal with the guilt history places on us only when we free ourselves from the ghosts.”

Richard Rodriguez, California Magazine, 1978

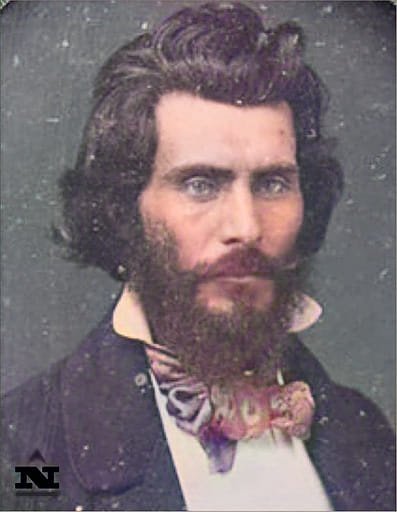

Joaquin Murrieta

Joaquin’s is a story told and retold in various forms and over the decades. Anyone who watched any of the Zorro movies or television series from 1920 to 1998 already has a part of the Murrieta story.

THE CORE OF HIS STORY

Joaquín Murrieta was representative of the many Sonorans from Northern Mexico who reached the valley to mine gold as early as 1850. Like many Sonorans, he came with family members and a wife to try their fortunes in the mines. Although successful for a short time, he was robbed and beaten by Yankee miners who killed his wife and brother. He turned for revenge to gambling and horse rustling, robberies, and killings.

Outrage at the bandit Joaquin grew until the California government organized a posse of 20+ California rangers to track down and capture him. Even they were confused and named five different Joaquins, setting a reward of $5,000 for the capture (of any). Harry Love and his rangers, hardened from time fighting Indians and Mexicans in Texas and eager for the reward, were given 30 days pay to bring him to “justice.” They tracked part of the gang to their camp in Arroyo Cantua where horses were held and then to their hideout in Tres Piedras (Three Rocks.) They encountered and shot all but two of the bandit there, claiming they killed Joaquin, his #2 Joaquin Valenzuela, and the dreaded Tres Dedos (Three Fingered Jack.)

As proof they had killed the Joaquin, they cut off his head and gathered affidavits as to its authenticity, claimed the reward and pay, and settled the matter. Unfortunately for historians, the head was exhibited and ultimately destroyed in the San Francisco earthquake of 1906. It was probably the head of another gang member.)

The Legend Grows

Joaquin was a common Mexican name, even among other members of the Murrieta family. Soon a Joaquin was blamed for almost everything.

In the period of 1852-1854 robberies, killings and mostly cattle rustling occurred all over the state by bandits. Although some were Yankee, the Mexican bandits gained statewide attention, and because so many (at least 9) had the name Joaquin, it was felt he was everywhere. More likely the bandit hero was the one identified by Sanger Chicano scholar Humberto Garza as Joaquin Murrieta Orozco, El Patrio, head of a statewide organization of horse thief gangs, at least eight of them with 200 members in all. Their success was in blending in with the mestizo population that secretly supported them and saw them as avengers against the injustice of the americanos.

Some contemporaries and authors didn’t believe he was killed at Three Rocks, that the affidavits were falsified to claim the reward or to throw the rangers off the trail of Joaquin, who had escaped. In another version, he traveled to Los Angeles, where he was shot and buried inside the house in which he was staying. Garza claims he went back to Sonora and lived to a ripe old age of 83. The entire town of Trincheras in the Mexican state of Sonora celebrates a Joaquin Murrieta Day and hundreds of people in Sonora and in California today claim a relationship to him.

A west hungry for tales like this and a public almost world-wide fascinated with western tales and romances ate up the story, promoted by news articles, books and plays—all with some version and flourishes. Joaquin’s exploits fed that thirst in books of the time purporting to be true histories, with radically different outcomes. What has survived of the story, is told and retold for different audiences and different times.

This Central Valley of California is named San Joaquin for the first Spanish explorer, Joaquin Moraga. The Joaquin name also has currency in Chicano history because of its symbolism of resistance. People name their sons Joaquin, name parks and places. Joaquin became the most notorious bloody bandit in California and a legend in the Mexican mind—to today.

The Annual Cabalgata to Three Rocks

The ultimate test of the endurance of the spirit of Joaquin Murrieta is that today his story is still celebrated, and has been for 40 years, on the valley’s west side, with a cabalgata (horse ride) from Madera to Cantua and Three Rocks. His spirit is evoked each year on the last Sunday of July through an impressive display of horsemanship and fiesta to call attention to today’s injustices, especially the plight of farmworkers and the immigrants who are now the valley’s latest victims of injustice.

The annual event was organized in 1978 by Sigur Christopherson, “Mexican Sigui,”a Murrieta enthusiast, Jesse Lopez of the Charros Association in Madera, and Don Julio Orosco of Mendota. It has attracted 20-200 riders each year in a three days pilgrimage that ends with prayers and fiesta and is one of the most photographed and filmed documentation of the enduring vaquero tradition in the valley.

Tiburcio Vásquez

Banditry didn’t stop with the end of the Murrieta gangs and then Yankees got into the act, more known for robbing stagecoaches and railroads than horses and cattle. Central valley played a part with its trails for stagecoaches and the introduction of rail and the Southern Pacific Railroad, which gained a reputation that angered those Yankee settlers.

The second famoso Mexican bandit was born in Monterrey and received an education, making him not one of the very downtrodden. He was a generation younger than Murrieta, born in 1854 the year Joaquín was supposedly captured and could have been influenced by that legendary hero. Vasquez became a sympathetic figure to his countrymen because he primarily robbed americanos, whom he believed had “stolen”’ California by Treaty after the Mexican American War. He credited incidents of discrimination and insults for his inspiration for revenge and denied shedding blood.

“A spirit of hatred and revenge took possession of me. I had numerous fights in defense of what I believed to be my rights and those of my countrymen. I believed we were being unjustly deprived of the social rights that belonged to us.”

A famed womanizer, with two periods spent in San Quintin, he was sought by reporters and visited by thousands in jail, including women bringing him flowers, before he was tried and hung in 1874 at age 37. He also became a symbol of resistance and pride in the areas around Monterey and Hanford.

The period of banditry mostly ended with Tiburcio Vásquez in 1975.

THE EARLY AMERICAN PERIOD: THE VALLEY TRANSFORMED 1849-1900

Garden of the Sun

The power of an image of Eden pulled many immigrants into the valley, seeking land.

They carved out Merced, Madera, Fresno, Tulare, Kings, Inyo, and Amador counties.

They connected the state through steamboats, pony express, stagecoach and railroads.

They granted land to settlers and the railroad.

They brought lumber from the mountains to the valley floor by flumes.

They irrigated the dry valley for crops with canals for irrigation.

The controlled the floods with dams.

They put their names on valley towns and streets and buildings.

They built the valley for themselves and marketed it as a “Garden of the Sun.” It was a garden planted with the seeds of Spain and Mexico.

In the valley the next-comers claimed the region for themselves, often fighting among each other over access to water, land titles, railroad lines, and public lands–and by the 1860s, over the politics of slavery and the Civil War. They created counties in the large central valley known first as Mariposa. Names of places began to change, mixed in with the Spanish heritage of the past or borrowed into English. Fresno, Madera and Tulare were joined by Kingsburg, Reedley, Firebaugh, and Visalia—the Río de los Reyes became the Kings River.

They connected the land by “iron horses,” railroads, and created a new camino de fierro through the valley with periodic stops that became towns. Their skills and some native power created the canals and flumes, bringing water and timber to the valley floor and turning it into what some promoters marketed to the nation as a “Garden of the Sun.”

Through sheer will they tamed the valley. They did it through droughts and floods, depressions nationwide, a panic of 1873, and a cattle industry that never fully recovered. The Valley became the primary source of agriculture for California and the nation, with over 230 crops cultivated by an increasingly multiethnic labor force.

TRANSFORMED BY CULTURES

The thousands-years-old cultures of native populations, trampled on by Spanish explorers and their Mexican followers with some help of mountain men prepared the way for the arrival of the newest “settlers.” Attracted to a new life and beginning, immigrants and refugees arrived in all parts of the valley to stake claims and create new communities of culture, adding to any colonias and barrios of those before them.

TRANSFORMED BY LAND

The Spanish and Mexican periods introduced invasive plants and American settlement exacerbated the change. The mix of wild animals didn’t fare well, especially the larger creatures, the herds of antelope and tule elk gone by 1885. The beaver had been hunted, but rabbits multiplied. The valley served as a large corral of feral horses and cattle, the new gold. The price of the greatest garden, trapping and habitat destruction, was the fate of many species.

Before this period there were vast plains to cross, the west side depopulated of natives for the missions, and rivers and lakes that were swollen from the runoff of snow in the mountains and dried up in the summers. Tulare Lake was the example of how most early persons experienced the valley.

BREWER SURVEY 1862-1864

William Brewer surveyed the area 1861-1864 for the new government, describing in great contemporary detail what the Spanish and Mexicans had before—a great plain 40-50 miles broad, desolate and without trees save along the river, without water during 9-10 months of the year and practically a desert. His survey in the winter of 1862 found the valley flooded, thousands of farms entirely underwater. Tulare Lake at its maximum size was half a million acres, a long shallow sea, described as the largest body of fresh water west of Mississippi. In 1863 the soil was dry and brown, no trees, but birds, insects, reptiles, and ground squirrels. It was unhealthy and infected with mosquitos in incredible numbers and of unparallel ferocity, and tarantulas by the thousands. Flowering depressions and hog wallows. He did note in 1864 that immigrants and farmers were taking over, cattle into the east and west foothills were vaquero country. He witnessed and praised the horsemanship of these vaqueros and recognized an area known for harboring lawless bandits. Following Gabriel Moraga’s earlier path, there still was that large swamp covered with rushes west to Tulare Lake.

The 1850 Swamp and Overflow Act created an opportunity to buy “waterlogged” land at a little over a dollar an acre, making Henry Miller one of the largest landowners in the western side of the Valley.

The Pre-emption Act of 1841 and Homestead Act of 1862 had established a sense of squatters’ rights among the land-hungry settlers who arrived. Squatters multiplied in the aftermath of the Gold Rush and especially after Civil War. The Land Act of 1850 granted undisputed land to homesteaders to colonize the valley. That reward, along with active promotions back East brought in the Americans from all backgrounds, especially to the valley for their skills in agriculture. Fresno County and Tulare County developed differently, Fresno fared greater in land speculation and Tulare with intensive homesteading.

During this era the marshes, swamps and sloughs were diked, drained, and cultivated. Tulare and Buena Vista lakes are now farmland requiring irrigation. Bakersfield was originally an island and oilfields are the newer crop. The California Aqueduct, the 44 miles concrete-lined canal visible from space, has allowed agribusiness to survive. Water and oil have become crops, subsidized, and the once barren west side, richest farming region in world now has problems. The native valley had begun its sacrifice to agriculture and settlement, carved, paved, and tapped out.

THERE HAS ALWAYS BEEN WATER IN THE VALLEY, NOT NECESSARILY IN THE RIGHT PLACE AT THE RIGHT TIME.

TRANSFORMED BY LAWS

The new California Commission created the 58 county structures by 1907 and the seat of government moved from Monterey to Sacramento. Two political interests developed in the state, norteños and sureños, with the Valley in the middle.

The first laws passed by the new Americanos was the Homestead Act and Foreign Miners Tax, especially a section that disallowed anyone with Indian or Mexican blood (also under 18 and mentally deficient) against testifying against whites. That privilege prevented legitimate claims against the Yankees who drove them out of their mines or abused them with lynching, beatings, and branding.

Legislation aimed specifically at the Chinese included even more restrictions, excluded from owning real estate or businesses, some employment and forbidden entry and naturalization.

TRANSFORMED BY MARKETS

The earlier period marked the beginning of the rancheros’ greatest prosperity, selling cattle for meat to the hungry miners, and the decline of the trade with the decline of mining. Not until railroads and refrigeration did the cattle prices soar again. The shrinking of cattle lands to farmlands transformed the valley as farming expanded during 1880-1900 from 100,000 acres to 400,000.

The change from sheep and cattle farming in this period was devastated by a drought in 1862-64 and a depression. The cattle industry never fully recovered, but the change to farming and an 1880 massive land boom eventually brought on large scale agriculture efficient for crop production. Valley farms became more like plantations, inviting exploitation of workers.

First, crops of wheat and barley turned to fruits and vegetables when railroad transport was available. Then raisins and cotton became kings. The Central Valley became a growing cornucopia of agricultural production, by the end of the decade carrying fruit, vegetables, and other commodities from the valley to faraway markets. Consequently, the valley became much more enmeshed in the domestic political economy, as well as developing an increasing sensitivity to international forces and events. The agricultural bounty of the valley faced a difficult and increasingly complicated issue:

WHERE TO FIND THE LABOR TO PERFORM THE WORK NECESSARY

TRANSFORMED BY RAILROADS

First steamboats on the fluctuating rivers, then in 1858 the Butterfield Overland Mail Route from St. Louis to San Francisco with relay stations, in 1861 the Pony Express delivering mail every 10 miles in 10 days—all created an infrastructure to connect California to itself and the nation at large. But no one did more to bring about change in social relations in California than the arrival of the railroad. It created a need for labor, brought in settlers, increased agriculture productions, and facilitated immigration, eventually from Mexico al norte.

So important to settlement and development, when the United States took over California, the Southern Pacific Railroad was granted more land than any other entity except the federal government. It was not only a railroad, an empire. New Yorker Leland Stanford first came to the gold fields and followed with success in businesses in San Francisco to become a wealthy industrialist. In 1868 he was one of the Big Four who created the Central Pacific Railroad and in 1868 purchased the Southern Pacific Railroad.

Branch lines and competing railroad lines became veins of the valley and developed settlement further, but these local lines were overshadowed by the transcontinental line completed in 1869

Cities developed because of the railroad creating stations and selling plots of land. It reached Fresno Station in 1872, Hanford and Goshen in 1877. Visalia, the valley’s largest settlement at the time, assumed the railroad would create a stop there, but when it refused to offer amenities that the railroad was asking, the stop went to Tulare instead. That change began the dynamic growth of Fresno as the valley’s hub.

Brochures attracted settlers, selling plots for settlers and reserving some west side areas for workers which became Chinatowns, especially in Fresno and Hanford. Promotional campaigns of “California on Wheels” shaped the valley’s towns and agriculture and connected them to other parts of the nation. Ads promoted the development for small farms, 10-40 acres with irrigation, to homestead and promoted them to “people of like faith and heritage.”

Many towns exist today because the Southern Pacific Railroad decided to ship from that point, opening markets and ended isolation, linking north and south and in the process gaining an all-powerful, corrupt control and reputation. For the Tulare area, the Mussel Slough incident in 1880 just five miles north of Hanford gave the Southern Pacific a reputation of cold blood anti-corporate greed when an armed encounter with aggrieved settlers left seven dead.

The railroad giants, the hustling land brokers, government manipulators struggled to control the valley’s caminos de fierro. Railroads also began to divide and define society, for the most part retaining the west side of the tracks for their laborers and the east side for growers, merchants, and professionals.

BOOKMARKS

Joaquin: Bloody Bandit of the Mother Lode, William B Secrest

The Life of Joaquin Murieta: The Brigand Chief of California, 1859 Police Gazette

Life and Adventures of Joaquin Murieta, Celebrated California Bandit, Yellow Bird (Rollin Ridge), 1854

Joaquin: Demystifying the Murrieta Legend, Humberto Garza, Sun House Publishing 2004

Joaquin Murrieta and his Horse Gangs, Frank Latta, Bear State Books, 1980

The Head of Joaquin Murrieta, Richard Rodriguez, California Magazine, July 1985

California Desperados 1835-1874, William B Secrest, Word Dancer Press, 2000

These Were the Vaqueros, Arnold Rojas, Alamar Media, originally published 1998